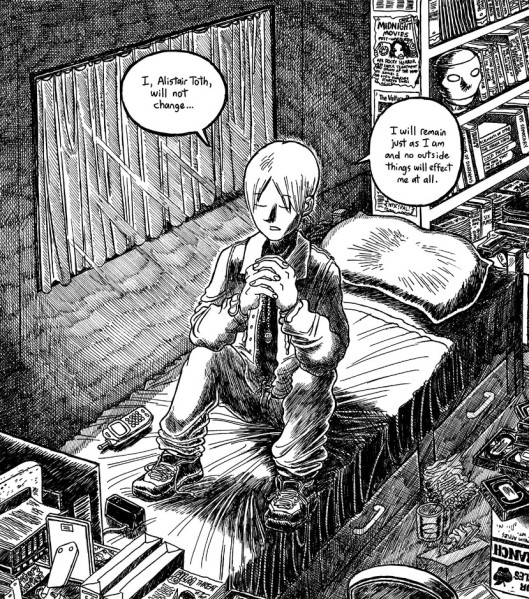

“Night Dog”

by Matthew M. Bartlett

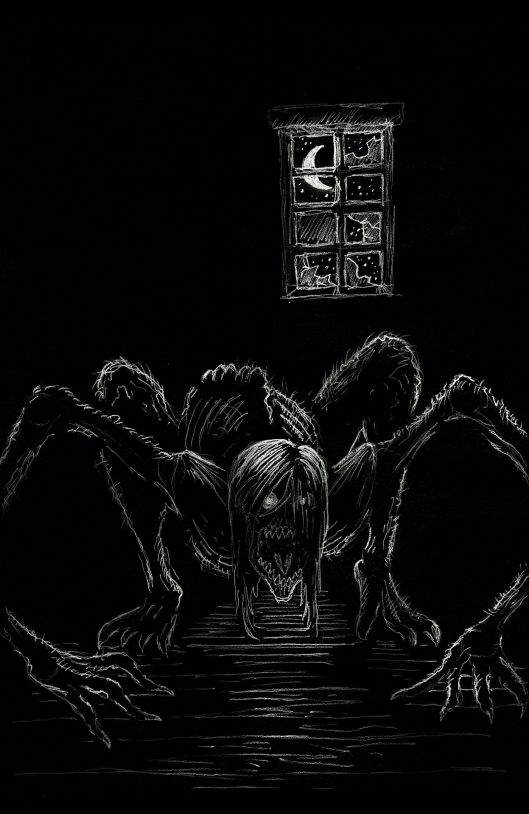

On numberless midnights, swatting away the night dogs leaping at the hem of my coat, their teeth flashing like crescent moons, I went in for night work at the flagship office of Annelid Industries International in the profusely wooded easternmost environs of Leeds, Massachusetts. Numberless midnights with the moon spilling its milklight down the forested mountain, numberless midnights crossing the parking lot to the gentle music of the cricket song and the fabric whisper of my pant legs. I’d badge myself in a half-hour early, fingernail the security code into the keypad, follow the lights of the red EXIT signs to my desk, where I would wear the light from the computer screen like a mask – a mask composed of spreadsheets and schedules – until 3 a.m. Then I’d rise, stretch, head to the kitchen, release from the vending machine a squashed, frosted thing to eat, brew a pot of coffee to wash it down. Mug in hand, I’d walk to the pedestrian bridge to watch the cars passing under while the coffee spread its warm fingers through my system. Then back to spreadsheets and schedules, mail alerts and messages, until 5 a.m., slouching through the double doors with the other night shift slouchers.

On one of those midnights, during an early March warm spell, one of the night dogs, a wiry, cat-like thing with an elongated snout and teeth like Hokusai mountains, got a curved claw caught in my jacket pocket. It whipped its body back and forth as I knelt, knee joints popping, and grabbed with my right hand the dog’s long ear, feeling its eye moving wildly beneath my palm. I tucked my thumb under the upper lip, closed my hand into a fist, and with my left hand wrested free the paw. Then with both hands I flung the beast into the reeds and rushed to the door. The other night dogs, bellies low to the ground, bared their teeth and inched at me, but none was foolhardy enough to lunge.

In the main hall, three offices from my own, I stopped to attend to a loosened shoelace, when I heard somewhere behind me the sound of a baby gasping and wailing. In the instant the sound registered, it was suddenly muffled, then cut off altogether. Leaving the lace hanging, I rose slowly, as silently as I could. I turned back, and peeked around the corner at the hall that led to the President’s Office. The corridor was dark, shadowed, interrupted with rhombus-shaped sections of weak light from the windows, its terminus black as pitch. I inched down the hall and, when I reached the President’s Office, I saw a rounded shadow spreading from under the door. My eyes began to adjust to the darkness, and the shadow revealed itself to be an expanding oblong patch of blood-soaked carpet. It glimmered in the half-light. Just before it reached the tip of my shoe, I turned and walked briskly back down the hall and around the corner, my breath popping from my lungs in little bursts.

I had learned quickly in my early days with Annelid Industries that intervening—even, perhaps especially, in the spirit of being a Samaritan—was not looked upon favorably by management. In May of my third year there I had happened to glance into a warren of cubicles and saw a man’s legs jutting from one of the open walls. I hurried over to find a youngish man, slender, nose flattened against the carpet, arms and legs splayed. I knelt, patted him on the shoulder with the palm of my hand, gently turned his head to the side. He was breathing. I called 911 from the man’s desk phone, told the operator to send the ambulance to the side door. When the EMTs arrived I opened the door and led them to the scene.

As the man was being lifted onto the stretcher, a coterie of frowning executives arrived, and one of them called the driver aside. They formed a tight circle, speaking in low voices, their faces tense and furrowed, while the EMTs loaded the man into the ambulance and, absent their driver, began to minister to him, talking him awake. A few moments later the driver, red-faced, was released from the convocation and called a brief but equally intense conference with his co-workers. Then two of the EMTs climbed into the ambulance and unloaded the stretcher, still bearing the stricken man. The driver and the one of the executives each grabbed a side rail and guided the stretcher through the double-doors that led to the executive offices and the auditorium hall.

About ten minutes later, the men brought back the tenantless stretcher, folded up the wheels, and deposited it back in the ambulance. The EMTs left without further ceremony. A few hours later I checked back at the man’s cubicle and saw it had been emptied of everything but a computer monitor, wires dangling from its back. The next day I was called to Human Resources.

Wright Knowles, the HR manager, a prim, mirthless man whose unironed shirt collars stuck up like toast points, handed me a written warning; vague, but biting, the intimation was that matters of perceived emergency were to be dispatched only by approved personnel, a club to which I absolutely did not belong and, if I continued on my present course, a club to which I would never belong. He signed it, pushed it over to me so that I could do likewise. I had never in my life received so much as a talking to, and I remember feeling chastened.

Now, I hurried back to my desk. I could feel my heart drumming, in my shoulders I felt it, and at my pulse points. I sat, caught my breath, did my best to try to settle into my work. The building was always quiet, but that night it was unusually so. From time to time the fluorescent lights in the hall flickered and the image on my monitor contracted briefly, shot a few lines of static across its lower section, then recovered. The phone rang shrilly once, and not again. When the red voicemail indicator lit up, I grabbed the receiver, typed in my code. I could hear only the sound of wind and faraway voices, calling in urgent tones. I strained to make out what they were saying, but it was no use. I hung up, dug back into the night’s tasks. I thought about the blood. I thought about that baby’s choked-off cry, and I thought about that warning from HR.

When my shift was nearly done, I checked the company email. There was only one new message. It was from the CEO himself, Wren Black.

To: AII-Corporate; AII-RDSci; AII-LSci; AII-ESO; AII-XXT

From: Wren_Black@AII.eso

Subject: Changes for A.I.I.

Good men and women of A.I.I.,

The time has come. Watch your email over the next few days for an invitation to a spectacular company event. The last of its kind took place forty-five years ago, in a different world. Come celebrate the latest step in the ever-unfolding saga of Annelid Industries International. Refreshments will be served. Attendance is mandatory. We can’t wait to see you there.

Together we will walk into the future.

For a reason I could not name, I was unnerved.

I put my finger on the mouse to close the mail window and an instant message popped up. The sender field was blank. The message was the address for the 24-hour Pan-Asian Buffet a quarter mile up the road. That was all.

***

The Asia-India-Ichiban Buffet was dimly lit and all but deserted. Red curtains and swirling neon representations of bowls and bottles adorned the rain-bubbled windows. The furious looking hostess, all in black, sickly slender but for the jutting protuberance of her pregnancy, was texting rapidly with both hands, her thumbs moving like the front legs of a fly, tears shining on her cheeks. In a red-cushioned booth by the sushi station, a young couple sat side-by-side, laughing in an unmistakably malicious manner, at what I could not tell. Across the room an old man in a fly-blown cardigan sat at a table by a window, alternating between looking glumly out at the grey boulevard and scraping noodles from his bowl with his finger and nudging them into his mouth.

I was just sitting down with my plate when a man slid in opposite me. Startled, I knocked over my water glass, and the man grabbed a pile of napkins and started to mop up. I grabbed his arm. He was bearded, slender, dressed in a light jacket and dark blue jeans.

“Wendell,” he said. He sounded sad. “Let me look at you.”

I let go his arm and winced. I don’t like to be stared at. He said, “The email came today, didn’t it, from Wren Black?”

“I’m afraid I don’t know who you are.”

“Wendell, we knew each other, a long time ago. I’m Byron Holeman. Look at me.”

The name meant nothing to me. I stared at his face, but I couldn’t reconcile his features. They were morphing, blurring, blending, eyes going square, then narrowing, their color changing from blue to brown to green and back. His mouth widened, pursed. His nose changed shape again and again as though animated with clay. My stomach clenched as though I was falling from a great height, and I fell back into the cushioned seat.

“That’s all right. I guess it’s not important, not now, anyway. The important thing now is this: the company event at A.I.I. – you don’t want to be there for it. You don’t want to be in Leeds. Wendell, you don’t want to be in Massachusetts. Go to Maine. Go to New York. When it’s all over…”

Who was this madman, I wondered, with a face that would not stay still, telling me I knew him, insisting I abandon my livelihood. “I…I need my job,” I said, ashamed at my obsequious stammer.

Holeman put his hands in the air, palms out. “Just listen to me for a few minutes, then I’ll leave you to your meal.”

I looked at my watch. “Go ahead,” I said.

“I worked there, at A.I.I., Wendell. In tech support. One day about four years ago I was going through old company footage, and I hacked my way into a password-protected file. I saw it, Wendell, the film of the 1969 meeting. I’ve never seen anything like it before. It was more of a ritual, a rite, than anything else. Wendell, I saw impossible things, terrible. Some of it…I’m still not sure it was real, but I don’t think it could have been faked. But it’s about to happen again. Annelid Industries International is old, far older than this country, older than you know. It started out as…as a different kind of concern. It was formed and founded by men with their hands in all sorts of forbidden things. They conjured up… Wendell, I hate to tell you, but I fear you’re under their thrall…under its thrall. Most everyone there is, too.”

And that was more than enough for me. “I’m sorry. I really am. But I have no idea what you’re saying to me. I think I’m going to leave.”

“Let me ask you a question,” he said. “Where do go when you leave work, Wendell?”

“I…” My mind conjured up blurred images of streets, houses, apartment buildings, high-rises, lawns, hedges, fences. They melded together into a chaos of glass, brick, wood, concrete, stone, and dirt. I could picture myself getting in my car, starting it, pulling the seatbelt across, driving out of the lot…and then? And then? Trying to focus made me dizzy, dropped a ball of nausea into my gut. I leaned over in the booth, grasped the edge of the table. “Why are you doing this to me?” I said.

“You helped me out when we were boys,” was his reply. He then pulled from his pocket a rolled up newspaper, spread it out on the table. “Read this,” he said, pointing to the upper left corner.

“It’s blank,” I said.

He looked down at the paper, looked back at me, stricken. “It’s…it was…the article about your disappearance.”

***

I had come to A.I.I. in those faraway days when applicants desirous of employment typed up their resumes on 24-lb paper, carefully constructed an accompanying cover letter, tri-folded the two into a business envelope, and deposited it in a metal mailbox to be taken away by blue-suited workers in white trucks, submitted to an extensive and complex process of culling and sorting and coding, nestled in bins with hundreds of thousands of other envelopes, divided and dispatched, and finally delivered to the hands of Personnel managers who would slide them open with small knives, examine their contents, and determine whether the sender warranted a personal audience.

Mine, apparently, had done the trick. I was called in for a night interview.

The A.I.I. Leeds campus consisted of two stone buildings that stood across a forested road from one another, connected by a pedestrian bridge. Behind the peaks of Building A rose a tree-covered mountain, forbiddingly caliginous and dark as pitch, except toward the peak, where pale yellow lights shone here and there, adorning the high trees with a suspicion of sepia. Behind Building B sprawled a crumbling, weed-split concrete wall about 8 feet high, its eastern and western edges obscured by thorny brambles. Beyond the wall rose the silos and pylons and staircase-encircled towers of some manner of factory, all of it lit up stark and bright like a mockery of daylight.

I drove under the bridge, turned into the lot, gave my name to the man in the gatehouse, and parked my Corvair between two hulking Jeep Cherokees. The receptionist bade me sit in a small waiting room, and then, after an interval, she called my name. When she stood, I noted that she was pregnant, very far along, too. She led me to the room where my interviewers waited. “Boy or girl?” I asked cheerfully.

She looked stricken and did not answer.

The conference room was sufficiently long to accommodate a long table with eighteen chairs, a dry-erase board, a ceiling-mounted projector and screen, and nothing else. The hiring manager, grey-haired, slender, in vest and jacket, and the head of the recruitment division, a young woman, blonde, in a tasteful business suit, also, I noticed, pregnant, sat at one end, each with a copy of my resume. I sat at the opposite end, clutching my own copy next to a mug of rapidly cooling coffee. The questions were standard, and my answers generated nods of assent and impressed looks between the two. At the close of the interview, the hiring manager took me aside and asked me whether I would assent to a polygraph examination and a routine physical, to be scheduled within the next seven days. I agreed. Having worked almost exclusively in manufacturing, never before in a business office, I assumed these preliminaries to be standard. Four days later I drove back in a frothing downpour for the three-hour testing period.

The personality test was long and unexpectedly stressful to navigate. Some prompts were repeated several times throughout, each time with slightly varied wording. Some were invasive. Of them, I still remember these:

You often consider humankind and its destiny

You feel involved while watching soap operas

You often contemplate the complexity of life

You willingly involve yourself in matters which engage your sympathies

For each I had to select agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, or disagree. The desired answers were not in every case easy to determine, but I did the best I could.

One week and one day later I had a job.

On my first day, I was supplied with several binders of lined notebook paper. Each page contained handwritten names, many nearly illegible, perhaps a phone number, a partial address. My task was to locate complete contact information and enter all of the data into a spreadsheet of my own design. These bits of information, I was told, represented Contractors. Their disciplines remained a mystery. Each could have one of twenty-eight codes assigned to him or her, codes that upper level managers would enter into my spreadsheet, and codes were also assigned to each of the company’s laboratory technicians, whose names I was not allowed to know.

I was to use the codes to match contractors to technicians and arrange meetings and set intermittent work schedules. I arranged hotel rooms, made dinner reservations, provided company as necessary – that is, if persuasion were needed or goodwill necessary to garner – based upon the contractor’s sexual preferences, no matter how odd or verboten, which were also noted in the spreadsheet.

As the main liaison and contact, I was also responsible for transporting Contractors from reception to the Laboratories. It worked like this: The red bulb on my desk console would flash three times. I would tap the pound sign twice to indicate I’d received the message, lock the computer, rise, and walk to Reception. The Contractor would be standing – there were no seats – perhaps studying the painting of lightning-lit caves that spanned the wall, perhaps looking out the window. His features would be obscured by a black hood that covered his head, obscuring his features but allowing him sufficient sight to navigate. I would walk the Contractor through the main hall, up the stairs, and to the pedestrian bridge. On the bridge would be a Laboratory Technician, features obscured in the same fashion. He would favor me with a slight nod, take custody of the Contractor and lead him through the door into Building B, where office staff were not permitted, just as Lab workers were denied access to the corporate offices of Building A. I would return to my desk and mark the Contractor’s arrival in the database.

This was my work. I did this for years. It was all I knew.

***

Holeman paid my bill and we left the buffet.

Over dinner he had told me about the contents of the article: a man, Wendell LaPorte, had left his house to go to the market, and did not return. His wife Laura filed a missing persons report. A lengthy interview with detectives indicated nothing about the family life that might have precipitated a sudden departure. He could not have simply fled, the wife insisted. He loved her, adored their son. He was in all outward appearance content. She would spend every resource she had to find her husband. She was certain something terrible must have befallen him. The police were keeping the investigation open, but one might easily infer from the article, Holeman told me, that it was not going to be aggressively pursued. After all, no one truly knows what is in a man’s heart.

Holeman told me about a follow-up article published a few months later. The man’s credit cards had not been used since his disappearance. His one living parent, his father, had received no contact from him, nor had his friends.

He was gone.

We stood under the awning in the rain. He took out his wallet, pulled from it a business card. He handed it to me. It read:

Byron Holeman

Programmer

Deprogrammer

It had a phone number and an email address and a street address in Stamford, Connecticut.

“Get in your car,” he said, “Head south on 91. When you get to…let’s say New Haven, call the number on the card. My secretary will provide you with an address. Go there and get yourself settled. Once I’m finished with my business in Leeds, I’ll join you and we’ll talk about getting you back to your family.”

A family, I thought. A family I…don’t remember. I promised him. And then I got in my car and drove straight to A.I.I. I was running late. I prefer to be early for work.

***

I parked my Corvair as I had done on a million midnights, innumerable midnights, infinitesimal midnights. The night dogs were unusually aggressive. I shouted at them, kicked them away, smacked at them with my hands. They whined. They yowled. When I got to the double doors, I turned to find them hunching, their tails curled up under their legs. They looked miserable, like they were witnessing some tragedy and were helpless to prevent it. In some strange way, I felt sorry for them.

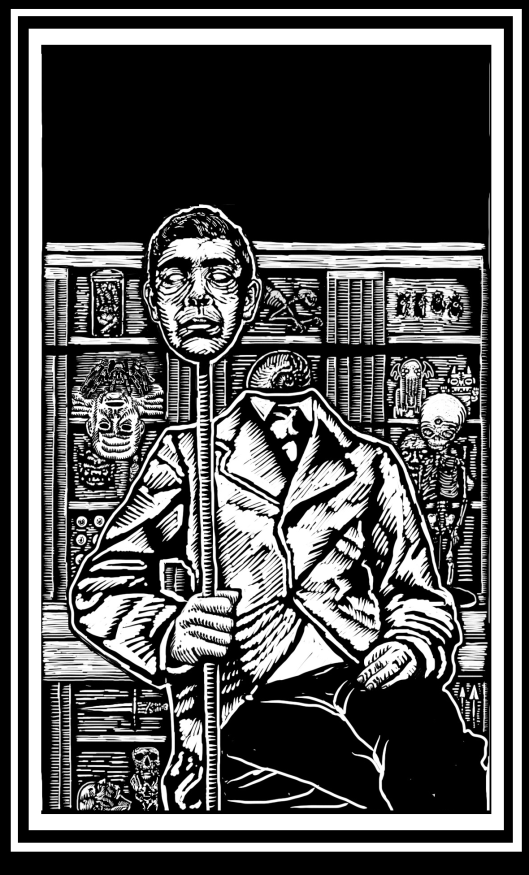

Going back to my desk, I took the route that led me through the East Hall. Lining the corridor in that hall is a gallery of framed portraits of the CEOs over the years. The first is from the late 1800s. A silver-tinted daguerreotype, copper-spotted at its corners, it depicts a steely-eyed, white haired man, broad of face, with runaway brows and a tight frown. On down the line, there are gaunt faces, fat faces, beards, waxed mustaches. Some of the men – all men, all white to the point of pastiness – are grinning blankly, others stern and serious. Apart from skin color, there is a unifying feature in all of the portraits. Something maybe, about their eyes – not their shape or their color, but the fierce imperative implied in their stares. Walking down the hall is something akin to time travel, but with an audience, all the eyes following you, like you’re in an office-themed variety of some malignant spook house.

I logged into my computer and looked at my email. There was one new message. It was addressed to me only, and the “From:” line was blank. The email consisted of a URL ending in a long string of numbers and letters and, under that, the number 77. I moved the cursor to the link, watched the arrow morph into a pointing white-gloved hand. I clicked.

Four video feeds appeared on the screen: the reception desk, empty; the main hallway, down which two security guards walked in apparent silence, looking straight ahead; the mostly empty parking lot; and the long, sky-lit atrium. I became unaccountably afraid that something awful, something grotesque and misshapen, might enter one of the frames. Dismissing that unwelcome thought, I noted that each video feed had a number at its bottom left, alongside a digital counter. I clicked the arrow at the bottom of the screen until I reached the 77th feed.

The display was crisp but for the occasional eruption of pixilation. It showed a well-appointed office, two walls filled top to bottom with glass-fronted bookshelves, the third a massive window that looked out to the wall of trees. I saw a desk, massive, gilded, with grey-veined black marble panels on the side and a gold-tooled black leather surface that reflected the soft light from the green-shaded lamp atop it. The desk was clear save a few scattered papers and a feathered pen and inkwell. Then a man walked in under the apparent location of the camera. From just the back of his head and his assured walk, I knew him to be Wren Black. He pulled back the chair, sat in it, and looked up at the camera, through it, straight into my eyes. I flinched and reached to close the browser, then stopped.

Wren Black leaned back in his chair. I could see only the man’s chin, above it the peak of his nose. The screen went red at the center of his shirt like a bright bulb under velvet. A flaw in the camera. No. His hands flew up and his long fingers pulled apart the shirt. I reared back. On Wren Black’s chest were two long, horizontal slashes, red and swollen. They opened to reveal large eyes, blood vessels burst in each one, splotches of red, pupils dilated. They blinked. Tears streaked down the man’s rib cage, and then the skin of his face went taut. His lips spread apart in a grimace, revealing clenched teeth. One of the teeth sprung out like a bullet, flying at the camera, hitting the lens, causing a curved crack to appear on the screen. Wren Black’s face went red, darker, purple. His neck flexed, spasmed, and then his head began to crumple. The skin of his face pinched inward and tore at the hairline, revealing a red expanse of muscle and skull. The chin and jaw were consumed by the neck, which was greedily chewing like an upturned mouth. A tongue, large and pink, lashed up over the nose, and the skin tore again at the forehead and the whole of his face was slurped down, leaving a bare skull whose eyes were now dull and lifeless. The skull bubbled as fissures formed all over its surface and it crumpled like sodden plaster. The now-headless Wren Black rose from behind his desk and walked toward the camera. The horrible eyes in his torso looked at me. Right at me. I closed the browser, kicked back my chair, and ran out into the hall.

I intended to turn right and run. My legs disobeyed me. They slowed, turned left. Ahead of me at an intersection I saw a throng of workers walking east. Everyone is here, I thought, the whole company is here. I twisted my torso from side to side, trying to turn, but it was no use. I joined them as they moved along the bridge. The doors to the forbidden laboratories swept open, the crowd poured through like milk.

The laboratories! I saw such things as I moved with the crowd!

Through one doorway I saw men shining penlights at a winged leech the size of a baseball glove buzzing madly about the brightly lit interior of a glass enclosure. Its wings were a translucent blur. Through another I saw a great conveyor belt teeming with all manner of teeth. Workers in surgical masks reached in from time to time, pulled out a tooth, threw in into a wheeled cart with canvas walls. Down a long hall to my left I saw a goat, upright, limping along on hind legs, using a cane with a brass human head to steady itself. I moved with the crowd, marveling at it all, into the auditorium.

The chairs were arranged in twelve curved rows each a half step up from the one below it, all facing a great marble rostrum that looked like it wouldn’t be out of place in some grand cemetery. On either side of the rostrum were three oak podiums. Behind those depended a massive screen, silver in color, which spanned the whole of the wall. From the high ceiling hung a lighting rig worthy of some grand concert hall, spotlights at the front facing this way and that, like snipers whose aim covered the whole of the stage. Unseen hands guided me to a chair near the back.

I sat, gripping the sides of my chair, my fingers, the only part of me I could control, tapping out arrhythmic beats of distress on its undersides. My colleagues and co-workers, half of them hooded, filtered into the room, murmuring. Then I heard a long, lowing sound, like that of a euphonium. The room rumbled. I felt my chair shake, my heart jostled madly in its cage, my brain rumbling in its quarters. The lights dimmed and the conversation hushed, then went silent.

The large screen depicted a crowded forest of thin trees, their branches bare and sagging. The camera swept across them, a cut, and the camera repeated its journey, faster and faster this repeated, creating a strobe effect. It was illusion, maybe, that in the sweep of the camera, the trees seemed to bend at previously undetectable joints along their scratched surfaces, bend and bow and dance. Somewhere in the blur of bending and bowing and dancing, shapes formed in the trees, hulking, pulsing, many-limbed. Toothless maws opened and closed on their rippling surfaces. The trees grew bubbling pustules, chancres, buboes. They dribbled pus and blood and gurgled lava.

Wren Black, the CEO of Annelid Industries International, strode through the room, down the center aisle, his head gone, a fire guttering at his neck, the flames red, purple, green. A plume of black smoke trailed behind him. His skin glowed red. The great eyes on his chest swept the room. Heads turned to mark his passage, and the crowd’s murmurs coalesced into a rhythmic hum.

He climbed the podium, stood before the crowd. His voice came in from the speakers around the room, introduced by a shriek of feedback.

When I came to this company and gave it its name, Annelid Industries International, the voice said, I felt like an interloper. In a sense, the company had existed for years, but without a home, without a name, without a singular vision. But all of its disparate divisions were profitable. Profitable and thriving. Their interests in the life sciences, in education, in entertainment, and in the esoteric, were interlocked like the interior of some great and vast and new machine, a machine that pulled in consumers and wrung from them gold. They summoned me to give them their name and to expand their power to this world and worlds beyond.

I vowed to honor their wishes. I expanded the company. I sought out powerful people, and I bought them, at the expense of profit, at the expense, I know, of profit-sharing checks. There were some who seethed about that. But those people are gone. The rest of you can laugh at them, at the naysayers, the same way that we laugh at a church that tries to thwart and stifle us, at the malignancy of a press that disseminates vituperative lies like the seeds of poison trees.

We grew. We took footholds in Germany. In Russia. In London. In Prague. And last month construction began on a Mideast headquarters in Qatar that will, when it is complete, rival the great palaces, the great temples of the world.

Wren Black stepped down from the podium, a wisp of smoke still trailing him as he began to walk up and down the aisles, his voice still emanating from the speakers.

A corporation is a man with many arms. Its reach may extend to a multitude of arenas: education, commerce, communication, biology, macro and micro, even into affairs of faith and of worship, of belief itself. But the essence of a corporation lies not in those arms, not in their reach, not in the grasp of the hands at their terminus. The essence lies in the man at the center. It is his vision that directs those hands, sends the nerve impulse down the arm, having the wherewithal to say grasp more firmly, having the wisdom to know when to say let go.

Consistency is the cornerstone of Annelid Industries. In those great glorious days when A.I.I. became a force in the world, I shone a light before me, a light that beamed from my immortal heart. That light revealed in the seemingly impassible tangles of the world a path. And you are the workers who clear that path, who cut and sweep aside the weeds, who push aside those who might hinder our progress. If it not for you, that path might be overtaken by the branches, woven and barbed, that threaten even today to diminish and extinguish that light.

It is time now that this body moves to the side of that path, lays down in the thicket, and passes from this life. I pledge to you that in my new incarnation I will continue to push this company into unheard of realms. My eyes will look out from a new face, and from its mouth will come forth my voice, the voice spoken through many mouths over many years. A corporation is a man with many arms, with many faces, but with one man at its center. It has been my life’s work to honor that tradition, to speak as one voice through many mouths. My time is past, but I am again and always part of the future. May it be so for all of you, when your time does come. Thank you for your true hearts, for your courage, and for your consistency.

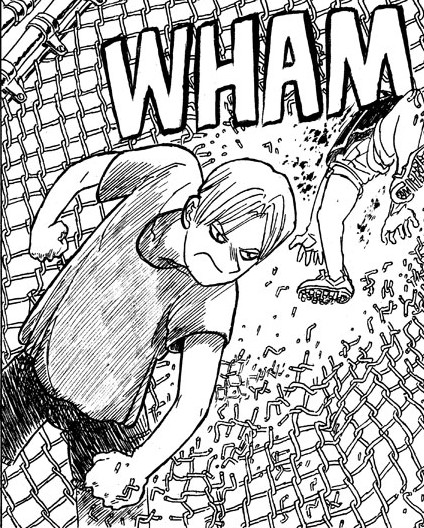

A shriek tore through the room. I thought at first it was some sort of shrill cheer. The room exploded in applause. Down the aisle, two security guards were dragging a man. As he was brought by me, he raised his face to the ceiling. Slender, bearded—it was Holeman, his features no longer shifting, but distorted by terror. He was clawing at the guards’ sleeves, crying. I have three daughters, he said, I have three little girls. They dragged him before Black and pushed him to the ground. He lurched forward and grabbed the hem of Black’s coat in both hands. The crowd gasped. Black pulled from his jacket a large serrated knife. He fell to one knee and jammed the knife into the side of Holeman’s throat. A great glut of blood shot out, spattering the front row. They wiped the blood from their eyes. Holeman was making a terrible sound, a ragged, gurgling wheeze. Then Black began to saw.

Holeman’s body sank to the carpet, his hands clutching at air. I saw his wedding ring. I saw the hangnail on his index finger. I saw the birthmark at the base of his thumb. Black grasped in his fist a clump of Holeman’s hair, raised the sawed off head to the crowd. I had never before seen a dead man’s face. It was white, slack, still. The mouth hung open. Wren Black placed the head on his shoulders, and the torn, mottled skin spat forth a cloud of pink smoke. There was a sound like bubbling. Holeman’s eyes popped out like jelly and fell in globs on his cheeks, replaced by eyes I knew, eyes I recognized – the eyes of all the portraits of the CEOs through the years: blazing, pitiless, yet dead.

Look upon me, said Wren Black.

We look upon you with devotion as you favor us with your eyes, the crowd murmured. Two seats to my left a woman in a black dress pushed her way to the aisle, fell to her knees, and began tearing at her eyelids, ripping them completely from her face, flinging them to the carpet. A man in the row in front of me began to do the same.

Favor us with your eyes, the crowd chanted.

Look upon me, commanded Wren Black.

Favor us.

Look upon me.

The image of the trees on the screen fizzled, went to white noise. The static seethed, then fizzled, revealing the blurred and pixilated image of a family. Before a green, bucolic backdrop a kind-eyed brunette woman in a green blouse smiled serenely. Her left hand was on the shoulder of a small towheaded boy in front of her, in a sweater vest, with gapped teeth, an embarrassed smile. Next to the woman, hand on the boy’s other shoulder…was me. I had hair, too, more brown than grey, and a healthy middle-aged weight that obscured my cheek bones. Coldness shot through my insides, from my stomach to my joints to my extremities, like an internal jet of water meant to rouse me from a faint. I felt the profound need to find the woman, to protect her and be protected by her. And the boy – I wanted to gather him into my arms shield him from danger. Something loosened its hold on me. I struggled to my feet. I may have been calling out, calling names I now cannot recall. People began to turn to look at me. Wren Black turned his horrible new head in my direction, glaring. I turned and bolted from the room as fast as I could go.

***

A corridor where there couldn’t possibly be a corridor, angling off of the pedestrian bridge. Looking out the windows from the bridge, you see black on black through a prism of kaleidoscopic black, cars floating like spotlight-eyed undersea creatures along the rain-drowned road beneath, but then, walking a few feet further, there it is, unmistakable, a lit corridor leading off into the night. I ran past it to the door the corporate offices, flashed my badge, two quick beeps and the red light blinked. They’d shut off my access. No choice, back the way I came was an army. I fled onto the impossible bridge. It was harshly lit, with a black linoleum floor and walls of large brick, painted over bright and brand-new white. Recessed lighting in the ceiling shot down in glinting cones, drawing pale circles on the floor. Ahead, the hall turned to the right, and when I turned the corner I found myself on a wet road, impenetrable tangles of bushes on either side. My feet skidded, and I landed hard on my back and slid. I got to my feet. Ahead of me, maybe less than a quarter mile away, I saw the lights of the A.I.I. Campus, of the bridge between the buildings. I scrambled to my feet, turned and ran. The faint ends of red searchlights wheeled in the sky like devils. The trees above me, leaning in, seemed to be placed in patterns, cloned, and re-cloned, stroboscopic, like a cartoon with repeating backdrops. Then I looked down, saw a cluster of eyes moving toward me, and stopped. I put my hands on my knees, stared back. The moonlight reflected off of those eyes, dozens of them, giving them the appearance of small green tunnels with echoing, unknown depths. White teeth glinted below each pair of eyes, emerging like the tips of knives stabbing out from the darkness. The night dogs loped into view, blocking the road before me. I could hear their eager breaths, almost smell the foul ichor puffing out like smoke from their gaping jaws. But then they turned, all but one, and faced away from me. The one night dog jutted his head in my direction, then turned and pointed his nose down the road, and looked back at me. The gesture was unmistakable. Follow, it said.

The dogs began to run and I began to follow, but then I glanced up the mountain and froze. The yellow lights that ringed the mountaintop were blinking, blinking and pulsing, growing larger and shrinking back, as trying to break free of their moorings. Great cracks like rifle fire echoed down the mountain, and the lights did break free, whatever massive beings that bore them wrenching themselves from the earth, black shadows peeling away from blacker shadows. Trees buckled as they began to descend. I looked back at the road. The lead dog again beckoned, the others began to trot, and then to run, and I fell in among them and ran.

A half-mile or so down the road I had to stop to regain my breath. I looked up and ahead of me I saw the dogs skid, scramble and stop. A grey door hovered in the middle of the road, flickering, contracting, glowing—willing itself into being. The dogs growled at the apparition. I kept running, right at the door, then jogged quickly to my right to bypass it. The door jogged too, and opened, revealing a blue tiled room—one of A.I.I.’s lavatories. Wren Black stepped into view, grabbed me by my collar, and flung me into the room, slamming the door even as the night dogs began hurling their bodies against it.

Wren pushed at my chest until I was backed up against the sink counter. Those blazing eyes glared from that dead but pinkening face. They glared…and then they softened. Wren Black released my collar, wiped his hands on his suitcoat. “Wendell,” he said. “I have a job for you, a job working closely with me, a job very important to the advancement of the company – we will provide you lab access, access, in fact, to the whole campus. This will, of course, involve a promotion and quite a substantial pay raise. You’ll be working directly with me, and with the top echelons of our division.”

Approved personnel.

Into my vision, blocking out everything, blocking out Wren Black, pushing away the blue tiles and the grey door, into my vision came the woman, her face, her hand resting gently on the shoulder of a boy, a man at her side, grinning blankly, a smile for the camera, a neutral smile. Was that man happy? Was he strong? Did he work among the top echelon? Was he approved personnel? I did not know. Those people were strangers to me. They might as well have been the picture that came with the frame, the one whose empty beaming faces you crumple and toss into the trash.

Look upon me.

The tiles began ungluing themselves from the wall and the floor, rising skyward, the roof tearing away to facilitate their passage. All around me, all around Wren Black they rose as he grinned at me, Holeman’s teeth gleaming in front of a swirling serpent’s tongue. The ceiling rose into the sky, a white rectangle spinning into the black night, just a speck, and then gone. I felt rain on my upturned face. I tasted it with my tongue. And then I too rose with the tiles, following them up, the blue-black night flaking and falling away around me, revealing in stipples a hint of the blinding-white infinity beyond it.

On numberless midnights with the moon spilling its milklight down the forested mountain, numberless midnights crossing the parking lot to the gentle music of the cricket song and the fabric whisper of my pant legs, a million midnights, innumerable midnights, infinitesimal midnights, I go in for night work at the flagship office of Annelid Industries International in the profusely wooded easternmost environs of Leeds, Massachusetts.

Matthew M. Bartlett is the author of Gateways to Abomination, Creeping Waves, Dead Air, and The Witch-Cult in Western Massachusetts. “Night Dog” was originally published in the anthology High Strange Horror (ed. Jonathan Raab) and reprinted in Creeping Waves. He was courteous enough to allow me to showcase that story here – it’s one of my favorites, and I’m sure you can see why. Please visit Matt at his (admittedly oft-neglected) blog, or check out a fan site here.